Marcus Aurelius, often described as the last good emperor of Rome, wrote a striking reflection on human work:

“At dawn, when you have trouble getting out of bed, tell yourself: I have to go to work—as a human being. What do I have to complain of, if I’m going to do what I was born for—the things I was brought into the world to do? Or is this what I was created for? To huddle under the blankets and stay warm?

So you were born to feel ‘nice’? Instead of doing things and experiencing them?

Don’t you see the plants, the birds, the ants and spiders and bees going about their individual tasks, putting the world in order, as best they can?

And you’re not willing to do your job as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands? You don’t love yourself enough. Or you’d love your nature too, and what it demands of you.”

What, then, makes someone want to huddle under the blankets rather than go out and do their job as a human being?

The question has been studied a lot across different literature. In this week’s note I want to offer one answer from Robert Karasek’s seminal 1979 paper, “Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain.”

Karasek set out to understand a deceptively simple problem: why do some jobs produce mental strain whilst others do not?

And what is the natural response to sustained mental strain? Precisely what Marcus Aurelius warned against: withdrawal, disengagement, and the desire to remain under the blankets.

I remember experiencing this at one point in my own career. I never questioned the value of work itself—I have been working since the age of seven or so and share views similar to Aurelius that humans are meant to work.

But each day during this period carried a dull sense of dread. It felt less like “I don’t want to work” and more like “I should be working on something else.”

Karasek’s Demand–Control Model

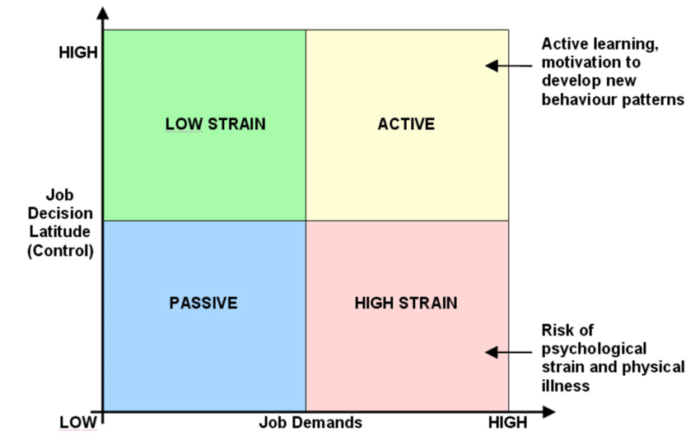

Karasek proposed that mental strain arises from the interaction of two core dimensions of work:

- Job demands: The psychological stressors involved in accomplishing the workload—time pressure, role conflict, and the sheer volume and intensity of tasks.

- Job decision latitude: The degree to which a worker can control how they do their work and use their skills. This includes autonomy in decision-making and the opportunity to develop and apply a broad range of abilities.

These are, I hope, intuitively familiar concepts.

The crucial insight was that they do not operate independently.

Karasek argued that the combination matters. The highest levels of mental strain occur in roles with high demands and low decision latitude—what he termed high-strain jobs.

By contrast, roles with high demands and high decision latitude can be challenging and absorbing rather than harmful.

The Findings

The results from his study strongly supported this hypothesis. Workers in high-demand, low-control jobs (assemblers, machine operators, garment stitchers) exhibited significantly higher levels of mental strain than those in high-demand, high-control roles such as physicians, engineers, and managers.

Notably, Karasek labelled the latter category active jobs. These roles were associated not with exhaustion, but with learning, engagement, and psychological growth. At the other end of the spectrum, passive jobs—low demand and low control—were linked to reduced initiative and diminished learning over time.

This brings to mind the often-quoted insight from Y Combinator’s CEO, Garry Tan: “At every job you should either learn or earn. Either is fine. Both is best. But if it’s neither, quit.”

Tan’s observation has circulated widely since he tweeted it in 2021. Karasek’s insight, however, suggests something more specific: the more learning (which derives from decision latitude) is removed from work, the greater the strain, regardless of how much you earn (with the caveat that this applies beyond what is needed to meet basic needs).

Why you may be disengaged at work

At the beginning, I asked why someone would huddle under the blankets when there is work to be done, or even when there is no work and finding it becomes the task.

Karasek helps us see why. When demands are high but decision latitude is low, effort no longer expresses agency. One is busy, sometimes intensely so, yet inwardly passive. Work becomes something that happens to you rather than something you do. In that condition, the instinct to withdraw—to huddle under the blankets and stay warm—is not laziness. It is a predictable psychological response.

By contrast, when high demands are paired with control, work takes on a different character. Difficulty becomes meaningful. Pressure sharpens rather than depletes. This comes closer to what Marcus Aurelius meant by “doing your job as a human being”: exercising judgement, deploying skill, and participating in the ordering of the world, however modest that contribution may be.

This also reframes the Stoic admonition to “love your nature”. To love one’s nature does not mean accepting any workload placed before you, but rather seeking conditions under which effort can express reason, choice, and growth. A role that denies decision latitude denies precisely those faculties that distinguish human work from mechanical labour.

Seen this way, the desire to escape certain forms of work is okay. Usually such rejection is a protest against work that demands much whilst allowing little. The appropriate answer, in my view, is not endurance alone, but discernment: moving, where possible, towards work that is both demanding and agentic.