In my application essay for my Masters in Finance programme, I wrote that a major reason for applying was to explore the questions of “what to do next” and “where to do it.” In my mind, there were two options:

Continue readingAuthor: David Alade (Page 1 of 18)

I am a student of the world. I learn, build and share.

When I started my career at PwC, one of the core messages I took away from the orientation month was that “your career is in your hands.” I also understood that consultancies are highly competitive environments where you can do incredible work with intelligent people and, more importantly, where grit, energy and creativity are well rewarded.

Continue readingJanuary’s news of the month centres on economic growth and the ecosystem in which it actually happens: a bold, ambitious one.

In a raw and unusually candid note about his time as Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak wrote that political pressure motivated him away from a strategic focus on economic growth and towards what he termed “affordability”. His own verdict was that this was a “[costly] mistake”. The note itself was written to draw the current Prime Minister, Keir Starmer’s, attention to what he believes are the same errors being repeated (link below).

Continue readingOver the years in my career, I’ve watched people sacrifice things I wouldn’t. I’ve also sacrificed things that, to others, made little sense to give up. I’m at peace with those choices — more than that, they are the source of the deepest satisfaction I take from my career.

Continue readingMarcus Aurelius, often described as the last good emperor of Rome, wrote a striking reflection on human work:

Continue reading“At dawn, when you have trouble getting out of bed, tell yourself: I have to go to work—as a human being. What do I have to complain of, if I’m going to do what I was born for—the things I was brought into the world to do? Or is this what I was created for? To huddle under the blankets and stay warm?

So you were born to feel ‘nice’? Instead of doing things and experiencing them?

Don’t you see the plants, the birds, the ants and spiders and bees going about their individual tasks, putting the world in order, as best they can?

And you’re not willing to do your job as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands? You don’t love yourself enough. Or you’d love your nature too, and what it demands of you.”

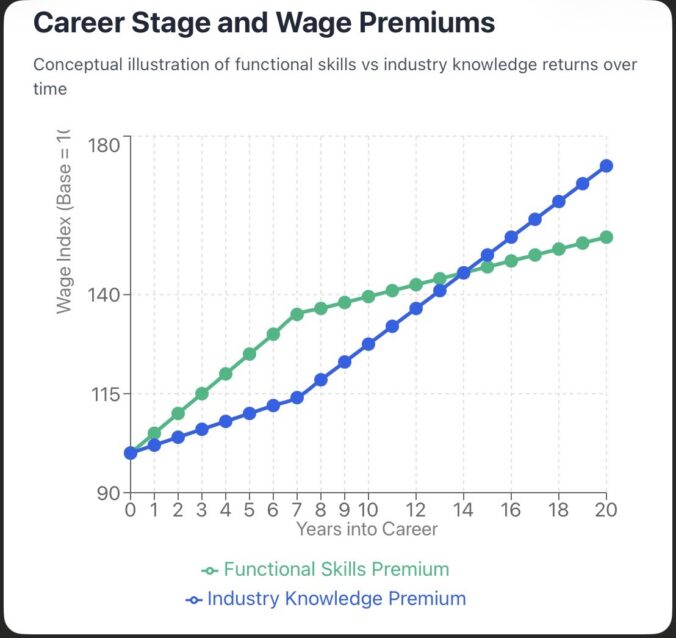

My friends and I, all with nearly a decade of work experience, have been discussing whether to deepen our commitment to a specific industry (even while doing different roles) or to maintain flexibility by moving across industries (even while doing the same type of work).

Most of us started our careers in consulting, which gave us early exposure to more than one industry. We are now thinking about which levers matter most for accelerating our careers over the next decade and beyond.

Continue reading2025 was, on balance, a good year for UK business. And I would be right to say It did not always feel that way in real time.

There were the familiar frustrations: taxes rose again, political promises went unmet, and the drought of IPO on the London Stock Exchange continued to prompt uncomfortable questions about Britain’s competitiveness.

Yet beneath the surface noise, the picture was far from bleak. The FTSE 100 delivered a historic 21% return in 2025, closing the year at record highs and crossing the 10,000 mark on the first trading day of 2026. UK companies raised over $8 billion in venture capital, with investment up 3% in the first half of 2025 compared with the second half of 2024 (HSBC). Meanwhile, 426,000 new companies were incorporated in H1 2025 (NatWest), including record AI companies – pointing to a broad-based recovery in entrepreneurial confidence.

So there were the bad and the good.

Continue readingAbout two years ago, I applied for a job at JP Morgan that I’d found on LinkedIn. I didn’t fit the profile for the role perfectly, but it was good enough that I was invited for the first recruiter call and then to the next interview. It was at this interview that the hiring manager and I concluded that I probably wasn’t well suited for the role.

A few weeks later, I was contacted for another interview at JP Morgan, but this time for a role I hadn’t applied to. I showed up, obviously. The hiring manager informed me that I’d been recommended for the role by the previous hiring manager, who thought I might fit their team better. Unfortunately, this role didn’t work out either.

Continue reading“Whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” — Matthew 13:12

Early in my career, before I knew it had been popularised as The Matthew Effect, I noticed this phenomenon. I captured it in an article as “it’s much easier to get ‘another success’ once you get the first one.”

Continue reading“I have done it before” is such a powerful anchor.Continue reading

You will not always have to do “it”, and when you are not doing “it”, it can be unnerving to think about not doing “it” in that moment. However, your ability to say, “Well, in the past, when I wanted to, I did it,” can be a strong anchor to help you escape that feeling. It is often also sufficient to get you through having to do “it” again.